Project 1: Discovery

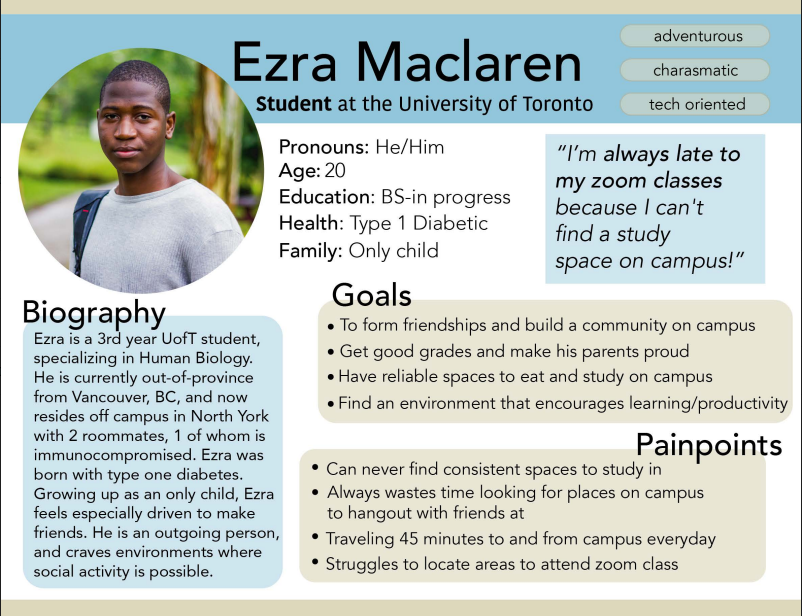

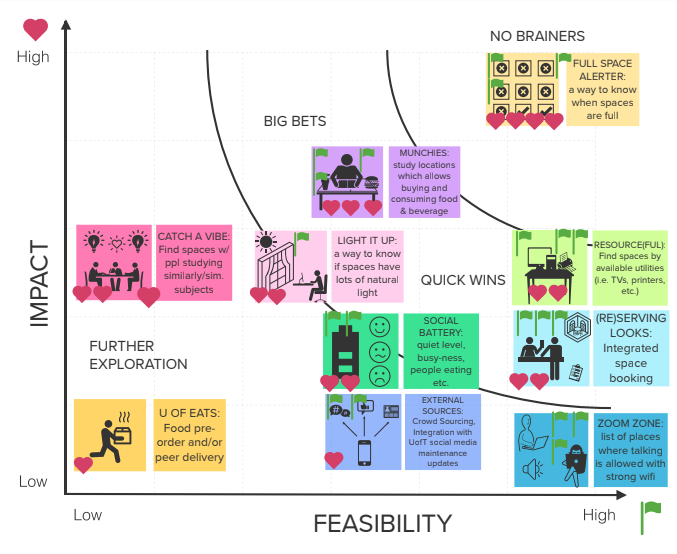

As our group formed and began preliminary discussions, we realized that all but one of us were new to the St. George campus in some way. Although pandemic-related frustrations entering and exiting Robarts often meant it was simplest to remain inside Bissell to study, we found ourselves wanting a change of scenery. But, we were left with the question so many of our peers, even those with experience on-campus, had asked before us: where should I go? And, even once you know where to go, how can you be sure that you won't run into capacity limits once you get there?

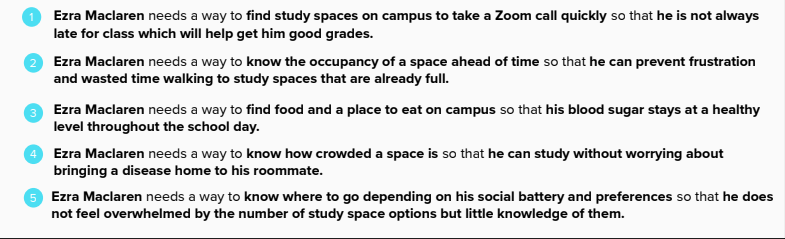

In this project, we conducted preliminary research into our target demographic – UTSG students– and how their studying is affected by their surroundings. We did this by conducting field observations and an anonymous survey focused on personal environmental preferences, both of which which turned out to provide data that was a little too general to extrapolate from. We also conducted secondary research by way of analyzing scholarly texts. The articles we found the most useful discussed the mental models people create when discovering and navigating around new places.